Jamel DuBois

|

Jamel DuBois was born in a grassy ditch somewhere along an Arkansas back road, and the adventure could only get better. He left home at age seventeen, crossed the country by rail and tore up his return ticket. He joined the Navy, and found that oceans are gateways not barriers. He became a magazine editor, then a world traveler and a big-game hunter. He dispatched a wild boar in hand-to-hand combat, and faced down a Cape buffalo in a horn-to-belt buckle encounter. He has set foot in six dozen countries on six continents, wrote numerous articles for many of the guns and hunting magazines, and writes killer novels authentically set in South Africa.

http://twilightanddarkness.weebly.com/index.html

jameldubois@dakotacom.net

|

New Title(s) from Jamel DuBois

Click on the thumbnail(s) above to learn more about the book(s) listed.

| Robert Blackwood is the greatest mystery author of all time. Just ask him. His mysteries are published in several languages and are adapted to motion pictures, all thanks to the efforts of his companion and literary agent, Jamie McCorkle. The pair works and plays in New Orleans, home of the popular pre-Easter Carnival celebration and Robert’s literary alter ego and star of his books, private detective Big Joe Holt. But things are not going well financially for the twosome when Bobby, as Jamie affectionately calls him, dries up creatively and fails to produce more mystery tales. However, author Bobby saves the day when he comes up with the ultimate mystery story concept and a bizarre plot to die for.

Excerpt

Word Count: 3010

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99

|

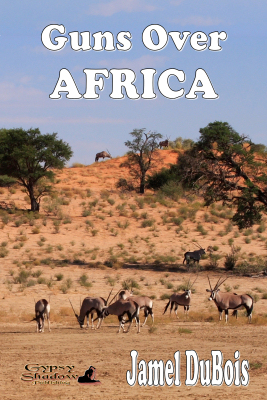

| Guns

Over Africa is an affirmation of sport hunting, and in this

context, hunting that contributes to the economy of developing

countries within the rules of international wildlife

conservation and preservation. This does not mean that the

hunter cannot enjoy the sport; it’s not all high-minded and only

for these obvious commercial and conservation benefits for other

than the hunter himself (or herself). For the hunter, trophy

mounts and memories resulting from such experiences flash back

the challenge, the competition, the failures, the successes, the

remorse, and the elation of the hunt. And they make last year,

or before, when the animals were taken, seem not so long ago,

and make the next hunt seem not so far away. Settings for these

safari accounts are Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Excerpt

Word Count: 42800

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99

|

| Thou shalt not kill. Neither shalt thou steal. These rules to live by are violated in some degree in all the stories in this collection: “Bring Me the Head of Kathleen Sullivan” relates the murder of a prominent Texas citizen. “Dominoes,” delicately positioned and when pressed into movement to nudge into the next one and that one into the next, results in a jumbled heap. In “Sad Songs,” the narrator is a songwriter-guitar player marked by hard work and hard times; and betrayal and lost love. “The Taking of Kaitlyn Peck” is the case of a young girl abducted on the way from school to her upscale neighborhood home. “Storm Clouds and Blue Skies,” one or the other, not both, mark the futures of these gypsy pilots. “Out of Focus.” Click, click, goes the mind of a killer, detailing revenge for a long endured and lying slur. “A Day At the Zoo,” certainly is no picnic, except for the man killers of a wildlife park in Africa.

Excerpt

Word Count: 38500

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ .99

|

| Excerpts |

Murder Gras

|

“Bobby, my man, you’ve got to snap out of whatever this is that has stifled your creativity.”

“Creativity, ha! I may have been clever, perhaps, but I don’t agree that I was ever provided the opportunity to be particularly creative.”

“And just what would you call it? The Robert Blackwood mysteries are clamored for all over the world. Of the fourteen books you have written, and so very creatively, I might add, four have been made into movies, and I’m negotiating with Silver Star Studios in Hollywood even as we speak, for two more. They are looking to make The Alabaster Cat and The Ghost of Chattanooga. And the books themselves—all fourteen have been translated into seven languages.”

“Damn the motion pictures. The directors are even less creative than myself. They feel they must give away the mystery with visual clues. There is no mystery, save for whether or not the plebian audience can understand the clues that I’m obligated to provide.”

“That plebian audience has made you rich, Bobby. You should not speak so unkindly about them.”

“They are little people with little lives.”

“That may be true, but it’s your stories that make them larger than life, if just for a little while, just long enough to marvel at your clever twists and turns.”

“See, even now you say ‘clever’ not ‘creative.’ ”

“Clever... creative... I won’t argue semantics with you Bobby. You are the Master wordsmith. I wouldn’t, and don’t, stand a chance in a verbal battle with you. But Bobby, you have to help me in dealing with Silver Star.”

“You’re my all-knowing literary agent. Your slice of my money is reason enough for you to handle that job, and for me not to get involved. After all, if I am indeed rich, then you are fifteen percent rich.”

“Bobby, I will be the first to admit that you have made me, if not wealthy, then extremely comfortable. I appreciate your talent and your generosity, but Bobby, it can’t continue this way. Except for royalties, which are diminishing, we’ll have no new money without these movie deals.”

“Those two books are done as far as I’m concerned. Ancient history! I’ve never written a script. A screenplay strips away the very character of the story; reduces it to talking heads and stage directions. I refuse to write a damned script for Silver Star Studios and that’s final.”

“Calm yourself. Bobby. Silver Star doesn’t want your name on the screenplay. It’s just that you haven’t written a single blessed thing for three years now. The studio suits are concerned about obtaining financing for these new films. They feel that with you out of the public eye, the moneymen won’t take a chance on bankrolling the films. They want you to write another book.”

“Is that all?”

“You mean you’ll do it? Do you have a story in mind? Pitch it to me. No, first let’s have a drink to celebrate the return of Robert Blackwood.”

“Perhaps ‘resurrection’ may be a better choice of word. I feel that I have been creatively dead these last three years.”

|

|

Back to Murder Gras |

Guns

Over Africa |

A Hunter's Tale—Alpha and Omega

I’ve had a good hunt, but I don’t hike the game trails any more. I’ve hung up my guns, but I hang on to the memories, and the memories are pretty good.

It would be romantic nonsense for me to claim having been a shooter and hunter all my life, although I often have thought of myself as such. The truth is in my early boyhood my shooting was restricted to a scant few .22 rimfire rounds at tin cans under the watchful eye of my father. It was his single-shot rifle, and cartridges were precious. We didn’t fire many on an outing. A box of fifty rounds was a treasure to be enjoyed sparingly over many months by the three of us—me, my older brother and our father.

Dad was left-handed. He instructed, “Here’s how you do it,” as he shouldered the rifle port-side. Although I am right-handed, I imitated him, and to this day I shoot a long gun left-handed.

I was fourteen before I owned my first rifle. I bargained with the gun shop, not realizing then I actually made the first contract of my life. I merely extracted a promise from the shop owner that he would not sell it to someone else if I made regular payments and paid it off in a specified time. I just wanted the rifle awfully much and knew that there was no chance of getting it except to come up with the twelve dollars on my own, but I never held such an enormous sum at one time. It was a proud day when I went into the shop with the last payment and took possession of the rifle.

In retrospect, I have to marvel I could do it at all. My parents were not involved; the handshake was between the dealer and me. It could not have happened in any but a small town, and not anywhere under today’s gun laws.

My father certainly was surprised when I brought the rifle home, and envious too. Mine was equipped with a five-round clip. I was to find his single-shot rifle was the reason a box of cartridges lasted him so long. My five fast repeat shots used up an allotment of cartridges much too quickly. Later on, when I traded the bolt-action in on a tubular-magazine pump rifle, I went broke feeding it.

I was shooting more, but had not become a hunter. I stalked the cunning Prince Albert tobacco can. With its reasonably large rectangular area it could absorb numerous hits before being transformed into artistic tin lacework. In that age of ecological innocence, I enjoyed the destruction of a Coke bottle with a well-placed shot. Once in a while I did shoot a squirrel, but to my shame, in light of my later education, I did not salvage the meat. Dad didn’t hunt, so I received no guidance in the art. Many were the times that we supplemented the family larder with fish from the Ohio River and its feeder creeks in my part of Western Kentucky, but we did not hunt. Why? I don’t know. It would have made sense for us to have hunted in those poor times but Mom didn’t clean the fish we caught; it was Dad’s chore. Perhaps he didn’t know how to skin and care for game. I learned how to myself much later in life.

When I left home at age seventeen, my rifle stayed behind. My father worked for the Illinois Central Railroad repair shops, and one of his benefits was courtesy rail passes for family. My rite of passage to independence was aided by steam-train passage from Kentucky to California. “You can’t take the rifle on the train,” Dad convinced me, so I left it behind. I think he just wanted my repeating rifle.

A cousin in California took me on my first hunts, once for ducks and once for deer, and I counted myself a hunter from that time on, although my hunting opportunities for the next several years were limited. The U. S. Navy disrupted my hunting education for a while, and later as a young-married, the economics of raising a family interfered with any sort of regular hunting. I was into midlife before I was exposed to, and became financially able to take advantage of, opportunities for serious hunting.

The milestone making it possible for me to partake at last in more than the occasional rabbit shoot or local deer hunt was my going to work at Petersen Publishing Company in Los Angeles. As a staff editor of

Guns & Ammo and Petersen’s Hunting magazines, I was exposed to hunting opportunities usually reserved, in my mind at least, for those who were financially well off. At times, hunting actually became part of my job. The windfall of being in the right place at the right time resulted in my participation in promotional hunts in Canada, Honduras, Spain and several states that, as far as my ever considering hunting in them, might as well have been foreign countries too. The perquisite carried over to my subsequent position as a field editor with Guns magazine after I moved to Arizona years later.

In 1983, Zeiss Optics Company arranged a safari in Zimbabwe to showcase some new products. The company selected four writers, myself among them, out of the entire United States and many sporting magazines, to be guests on the promotional trip. In 1985, the South African Tourism Board selected seven journalists representing print and broadcast media from the United States and Canada to investigate the recreational opportunities of South Africa. I was one of only three magazine editors to be part of the group, the others being newspapermen or television sports-host figures.

Like an addict, once injected with these complimentary doses of African safari, I put my own dollars into repeated fixes for my treatment. My domestic hunting also did not depend entirely on advertisers’ promotional junkets. I discovered hunting in general, and safaris in particular, are not really bank-breaking habits to support. I have been in safari and hunting camps with workingmen who have saved for their “once-in-a-lifetime” hunts, and who started planning for their “never-in-their-wildest-dreams” return hunts before ever leaving camp. I was one of them.

It was on my fourth or fifth safari I was forced to face up to the prospect of retiring from hunting altogether. One other legacy from my father, in addition to the handicap of shooting left-handed, was a flaw in my respiratory system. He choked constantly on the coal dust associated with his railroad job, and smoked heavily as well. Both conditions contributed to his dying of emphysema. I contracted asthma while I was of first-grade age, and in light of recent studies, I think my affliction was the result of the secondhand cigarette smoke filling our house.

I never smoked myself, but as my age progressed so did the asthma until it reached the irreversible stage and my doctor started referring to the condition as emphysema. Even before though, the advancing asthma and its treatment were taking their toll on my shooting. It’s difficult holding a rifle steady when your breath comes in labored gasps. I could relieve the difficult breathing temporarily with an inhaled medication, but this caused my heart-rate to accelerate—another condition adversely affecting rifle marksmanship.

Personal retirement has occurred in other sports where the participant holds too much respect for the game to allow it to be demeaned by an individual poor performance: a major league baseball pitcher or NFL quarterback recognizes the early warnings of no longer being able to place the ball where he intends it, and refuses, out of pride, to hang on for another season. With hunting, the indicators suggesting or dictating retirement come gradually, perhaps over two or three or more seasons. The early warnings can be put down simply to having a bad day, and in fact, they are only occasionally poor performing days, until they occur successively closer together. My unavoidable decision was to quit the game.

Though I have hunted much of the world and gathered experiences usually available only to a small fraternity, this collection of hunting accounts is limited to my personal memories of Africa. It is intended as an affirmation of sport hunting and its many rewards, even for those who start later and close out their season sooner than they might have liked. Rather than lament the hunting opportunities now lost, I celebrate the ones I have been afforded.

|

|

Back to Guns Over Africa |

|

|

Sixes and Eights |

Bring Me the Head of Kathleen Sullivan

Peggy Vasquez, saddened and overcome at her mother’s recent and brutal demise, lost conscious connection to the ongoing eulogy being presented at the graveside. Friends and dignitaries, in seemingly unending succession, stepped to the speaker’s stand, which many required for physical support of their grief and disbelief. The respectful attendees to the funeral service offered condolences to the remaining family of Kathleen Sullivan, and praised Kathleen’s good works and the woman herself whose name had gained national prominence.

Peggy was the only of Kathleen’s six children residing in McAllen where Kathleen also lived—lived until last week. Peggy’s siblings, one sister and four brothers, had scattered around the country over the years as dictated by jobs and careers and marriages. Peggy was the second child. Her older sister lived in Oklahoma; two brothers were in Denver, one in Florida and one in Oregon. The family was close, just not close together. Peggy never considered leaving McAllen for any reason, because her mother lived there, and had lived alone and independently since the earlier death of Peggy’s father.

Peggy married locally, to Manuel Vasquez, and never really considered, as her siblings did, hers a mixed marriage. North Americans and Mexicans interacted freely in the Texas border and near-border towns. Peggy knew Manny when he was a young boy working at the Sullivan ranch years before. She and Manny grew up together, attending the same school, the same church, and the same social functions. Kathleen never objected to Peggy loving Manny, and their lightly tanned offspring, a girl and two boys, were Kathleen’s grandmotherly pride and joy. Kathleen often had said so.

Now the family was gathered again, the first time all had been together since their father’s funeral eight years before. There were more Sullivans now, additional grandchildren having been born who Grandfather Sean Sullivan never had the chance to know. Kathleen visited her sons and daughters-in-law at all the recent births, representing herself and her longtime lover, husband and family patriarch, Sean. Only Kathleen’s oldest child, Darina, ushered in no grandchildren, having failed to live up to the productive name Kathleen had wished on her. Darina, the account executive, and her husband, the airline pilot, were at the funeral along with all the Sullivan boys and their wives and children.

Darina sought out Peggy following the end of the service.

Peggy wore a short black dress, black hose and black low heel shoes. The hose and heels came from her existing wardrobe; the dress was purchased for the occasion, a one-time wearing. Peggy would put it away, but not ever discard it. It was part of her mother-memories. The veil covering Peggy’s freckled face throughout the ceremony was thrown back over her head, revealing a shock of coppery hair. Tears concealed by the veil in place had run dry.

She embraced her older sister.

“Peggy, how could you have let this happen?”

“Me, Darina? You blame me for this? Mother was murdered, in her own home, and it was sickening. I found her because she didn’t answer my calls and I went to her condo. How in God’s name can you hold me responsible?”

“I’m sorry Peggy. Of course I didn’t mean it the way it must have sounded. It’s just been so terrible. I just can’t imagine someone doing something so horrible to Mom. And I can only imagine what you have gone through here alone. And as painful as I know it will be, I have to know what happened, when you feel like talking about it.”

“I think I can tell you now. I know the boys will ask the same things, but I don’t know if I can face you all at once. I don’t know if you all really want the truth.”

“Oh, my dear little sister, I do want to know. I have to know, and I want you to know how much I love you too. Tell me about how Mom was days ago, weeks ago; how she was and what she did. I am so sorry I live so far away. I’m so grateful Mom had you here to care for her. All of us always loved you for remaining with Mom while we all moved away. By rights, as the oldest, it should have been me who stayed here. I should have been the one taking care of her.”

“And you think if you had been here Mom would still be alive. Your implication is somehow I failed her and you and all the rest. Is that what you’re saying?”

“No, no, no! Peggy. I don’t mean such an implication at all. If anything, I wish I could have saved you from being the one who found her. What you must have gone through... I simply cannot even comprehend.”

|

|

Back to Sixes and Eights |

| |

|

top |

| |

|