Steven James Foreman

|

Steve is British and has lived in Africa for more than 20

years. He works in mainly conflict affected regions as a

top-level Security and Risk Manager/Consultant.

WEBSITE: https://bushleader.wordpress.com/

FACEBOOK:

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100010379619944

BLOG: https://bushleader.wordpress.com/ |

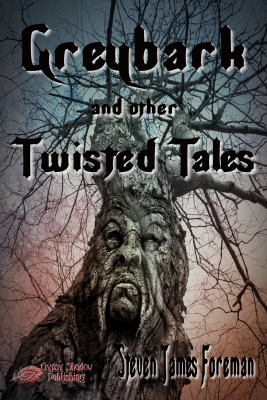

New Title(s) from Steven James Foreman

Order The Greybark Print Book Today!

Click on the thumbnail(s) above to learn more about the book(s) listed.

|

Greybark is a collection of published short

stories that previously appeared in both print and online

publications, all brought together now in one book. Here you

will find short stories of horror and hauntings, tales of

strange beings and vampires and talking trees, accounts of death

and destruction, fatal encounters with ghosts and monsters and

mythical creatures, and crime mysteries with unexpected twists

in the tales. This is a book to keep by your bedside for a quick

read before lights out, or to take with you when travelling, to

dip into at random whenever you have half-an-hour to fill or do

not have the time to read a full-length novel. Don’t leave home

without it!

Several of the stories in this book originally appeared in the

anthologies Beneath the Surface and Trips to the Dark Side, both

published by Gypsy Shadow Publishing and currently out of print.

Beneath the Surface was voted third out of the 64 books

considered by the Preditors and Editors Poll 2012 in the

Anthologies category.

Excerpt

Word Count: 94770

Buy at:

Smashwords (all formats) ~

Barnes and Noble ~

Amazon

Price: $ 5.99

|

|

Order Greybark and other Twisted Tales in Print today!

(ISBN: 978-1-61950-331-1)

|

| |

|

| Excerpts |

Greybark and other Twisted

Tales |

Greybark

First published in Aphelion Magazine (2014)

Sara straightened up from loading the dishwasher, tucked a

strand of loose blonde hair back into her headscarf and looked

out the kitchen window of their new house. At the bottom of the

long back garden, just inside the fence, stood a huge old oak

tree, and standing next to it Sara could see her five-year-old

daughter, Penny, dressed like a tomboy in denim jeans and

wearing Bubblegum trainers. The girl’s lips were moving, and she

appeared to be talking to someone, but, as Sara would have

expected, there was no one else around. The few neighbours who

had so far moved into the other new houses nearby had no

children of Penny’s age, and at present, Penny was an only

child.

Sara wondered if Penny had suddenly got an imaginary friend. She

had heard that such playmates were often conjured up by

children—especially those who had no siblings.

She said nothing to Penny when the girl came in a short while

later, but made a mental note to keep an eye on this

development.

A few days later, when Sara went out into the afternoon sun to

hang clothes on the washing line, she actually heard Penny

speaking. The words were faint and lisping—not quite a whisper,

but slightly secretive. Sara feigned fussing with the laundry

basket and clothes pegs as she kept an eye on her daughter. The

girl appeared to be having a one-sided conversation. Sara

dropped her husband’s shirt back into the basket and strolled

over to her daughter. As she approached, Penny glanced around

and fell silent.

“Hi, baby,” said Sara in a light-hearted tone. “I thought I

heard you speaking. Who were you talking to?”

“No one, Mummy,” the girl replied. “Just playing with my dolls,

that’s all.”

“Oh, okay, darling, come on, come and wash your hands. There are

some milk and cookies on the kitchen table.”

Sara mentioned this development to David, her husband, when he

came home from the city that evening.

“I am sure it’s nothing,” David responded, as he sat down in an

armchair and shook open a copy of The Financial Times. “I have

heard about imaginary friends before. It’s just a phase that

will pass, I am certain.”

Over the next few weeks, however, Sara became increasingly

concerned about the amount of time Penny spent at the bottom of

the garden in the afternoons after she came home from

kindergarten, talking to her imaginary friend.

zzz

The fence at the bottom of Sara and David’s garden separated

their 50-metre manicured lawn from a huge area of deep deciduous

woodland that stretched away left and right for several miles.

Named Hartdown Woods, not long before scores of trees along the

fringes of the woods had been cut back to make way for the

twenty new detached houses now lined up along Hartdown Drive.

David, a fairly wealthy property developer, had not only built

the houses, he had set one aside for himself; his family was the

first to move into Hartdown Drive. Even now, several of the

other houses were still vacant and up for sale.

The only exception to the woodland clearance along the rear

boundaries of the twenty houses was the huge oak tree. The tree

was spared because of its great size and age, and because it

straddled the plot survey line. David had decided rather than

cut it down or reduce the size of the plot—thereby altering the

value of the land—his building contractors would dog-leg the

chain-link fence behind it, and therefore the tree stood within

their back garden.

zzz

“I am really getting worried about this,” Sara confided to her

husband one evening. “I mean, it is not just that she has an

imaginary friend; as you said, a lot of kids have those, but

Penny seems to be becoming secretive, and when I ask her about

her friend, she becomes silent and sullen.” Sara frowned. “And I

have only ever seen or heard her talking at the bottom of the

garden… never in the house or in her bedroom.”

“Well,” David responded. “Let’s have a word with her

kindergarten teacher at school; see if she has noticed

anything.”

The next day, instead of Sara just dropping Penny off at the

school gates, David took the morning off work and accompanied

her, and he and Sara went into the school offices where they

asked to speak with Penny’s teacher, Miss Spencer.

“No, I have never seen Penny having any one-sided

conversations,” the teacher replied to Sara’s question. “She is

just a normal, happy little girl, with plenty of playmates in

class. But if you are really worried, we have a school

counsellor you could speak to. She is a qualified psychologist.”

David and Sara glanced at each other. “I don’t know,” David

said. “A psychiatrist? It seems a bit extreme.”

Miss Spencer gave a reassuring laugh. “Doctor Jane Archer is not

a psychiatrist!” she shook her head gently. “She is a student

counsellor with a degree in psychology. So do not be alarmed.

She will be able to explain better about an imaginary friend and

the effect it has on a child.”

So David and Sara agreed, and Miss Spencer led them down the

corridor to Doctor Archer’s office.

“Imaginary companions are an integral part of many children’s’

lives,” Jane Archer explained, once David and Sara were seated

and had outlined their concerns to her. “They provide comfort in

times of stress, companionship, someone to boss around when they

feel powerless, but often they can be a role-model or an idol.

Most important, an imaginary companion is a tool young children

use to help them make sense of the adult world. So, your child’s

best friend may look just like her, eat the same foods, and

share the same interests.” Jane paused for a moment.

“While some child development professionals still believe that

the presence of imaginary friends past early childhood signals a

serious psychiatric disorder,” Jane explained and smiled

reassuringly, “I firmly believe that is not the case with

Penny.”

“You mean some kids who have imaginary friends can become

psychopaths?” Sara asked, sitting forward with a worried frown

upon her face.

“No, I didn’t say that, Sara,” Jane replied.

“I think I understand,” David interjected, “but from what my

wife has seen, this

imaginary friend only seems to surface in our back garden. Even

her teacher, Miss Spencer, says that she has never seen Penny

interact in class with anything or anyone invisible.”

“Well, maybe she only needs the friend when she is lonely… or

should I say, alone,” Jane glanced at Sara, who was about to

protest at the word lonely. “In other words, she gets enough

companionship at kindergarten and from her parents in the home,

but just needs a playmate when she is alone in the back garden.”

“I guess that could be it,” David muttered, leaning forward and

staring at his feet.

“Look,” Jane continued, brightly, “if you are still

uncomfortable about Penny having an invisible friend, you should

take comfort in knowing that research has consistently shown

that kids actually know these friends are not real and that they

will outgrow their need for such companionship with time. You

can determine whether you want to go along with Penny’s

imaginary friend or not, just by letting the friendship continue

on its own course, to the point where Penny may even discuss the

friendship with you, what they played or said to each other, as

she would if it were a real friend from kindergarten; she may

even tell you the friend’s name or something about him or her…

but you should not be insistent about Penny not pretending to

have such a friend, or you could create stress and turmoil for

her.”

With all this information at hand, David and Sara decided to

follow Jane Archer’s advice, and let things run their course.

Only a few days later, one afternoon when Sara was in the garden

clipping some flowers for the dining table vase, she heard Penny

raising her voice. She spun around in time to see Penny stamping

her foot petulantly and wagging her finger.

“No, it is not fair, it is not their fault!” Penny shouted and

burst into tears.

Sara dropped her pruning clippers and ran down the lawn to where

Penny stood sobbing. She swept the child into her arms, soothing

and comforting as only a loving mother could. “There, there,

baby. Whatever is the matter?” She smoothed the child’s hair.

“What is wrong, Penny?”

Penny’s sobbing subsided under the warm embrace of her mother.

Still choking back tears, the girl replied. “He said he wanted

to hurt you and daddy, ’cos you took his friends away from him!”

Sara carried her daughter back to the house and sat down next to

her on the sofa in the living room.

“Who said he wanted to hurt us, baby? Who were you talking to?”

“Greybark. His name is Greybark.”

“Penny, darling, is Greybark your imaginary friend? The one I

have heard you speaking to, is that who you mean?”

“No Mummy, Greybark is the big tree. He talks to me.” The girl’s

chest heaved twice; the air catching in the back of her throat,

as the final sobs faded.

Sara clamped a hand to her mouth to hold back a cry. She

breathed in and out heavily for a few moments before regaining

her composure.

Sara fetched a glass of water from the kitchen, passed it to her

daughter and then picked up the phone nearby.

“David? Are you able to leave work early and come home? I am

worried about Penny.”

“What’s wrong, is she sick?” David’s voice was concerned.

“No… well, not really. It’s this imaginary friend of hers. There

has been—a development. I cannot explain on the phone, but you

need to be here to hear this.”

|

Back to Greybark

|

| |

| |

| top |

|